Why Does Developing on Kubernetes Suck?

Let me count the ways

Kubernetes has changed the way I operate software. Whole classes of production problems have disappeared–arguably to be replaced by others. But such is the way of the world. All told I’m happier operating a microservices app today than I was before I started using Kubernetes.

When I’m writing software, though, Kuberentes has only made things harder. In this post I want to walk through all of the problems I have encountered developing software on Kubernetes. Full disclosure: While I work on Tilt as part of my job, which we have designed to solve some of these problems, another part of my job is writing software that runs on Kubernetes. When there’s another tool that solves a problem better than Tilt, I’ll use that.

So, how does developing on Kubernetes suck? Let me count the ways.

Myriad Dev Environments

Minikube, MicroK8s, Docker for Mac, KIND, the list kind of goes on. All of these are local Kubernetes environments. In other words: they’re Kubernetes, but on your laptop. Instead of having to go out to the network to talk to a big Kubernetes cluster (that might be interacting with production data) you can spin up a small cluster on your laptop to check things out.

The problem comes when you want to run code/Kubernetes configs on multiple of these clusters because they each have their own… let’s call them quirks. They don’t behave identically to one another, or identically to a real Kubernetes cluster. I won’t enumerate these discrepancies here, but I’ll refer to this problem throughout this blog post when discussing thorny issues like networking and authentication.

There’s no tool I’m aware of that solves these problems aside from just doing your development in a real Kubernetes cluster in the cloud, which is the way I prefer to work these days. If you’re in the market for a local dev cluster we recently published a guide to choosing a dev cluster to help make sense of all the options.

Permissions/Authentication

If you’re developing software on Kubernetes, you’re probably using Kubernetes in production. If you’re using Kubernetes in production, you probably have locked down authentication settings. For example, a common set up is to only allow your developers to access to create/edit objects in one namespace. To do this you need a bunch of things set up:

- A role

- A rolebinding

- A secret

This works great if you’re using a “real” Kubernetes cluster, but as soon as you start using a local Kuberentes setup, things get weird. Remember all those local dev environments? Well turns out some of them handle RBAC very differently than you might expect. I ran into an issue where kubeadm had access control set to allow everything. As a result, I had false confidence going to prod that my settings actually restricted permissions, when in fact they didn’t. Granted, kubeadm-dind-cluster has since been deprecated, but it goes to show that not all Kubernetes clusters are created equal. I also ran in to another problem trying to reproduce the issue on Docker for Mac’s Kubernetes cluster where RBAC rules were not enforced.

Testing things like NetworkPolicies is also fraught. NetworkPolicies don’t work at all on Docker for Mac or microk8s and require a special flag for Minikube. The troubles in networking land don’t end there.

Network Debugging

Network ingress is one of the most important things that Kubernetes does. Unfortunately, ingress is implemented differently by different cloud providers and is, as a result, very difficult to test. The different implementations also support different extensions, often configured with labels, which are definitely not portable between environments. I’m lucky enough to have access to a staging cluster to test ingress changes, but even then changes can take 30 minutes to take effect and can result in inscrutable error messages. If you’re on a local Kubernetes environment, you’re pretty much out of luck.

Networking is my least favorite thing to work on in Kubernetes, and the area that I think still needs the most love. There are a couple tools that help out, however.

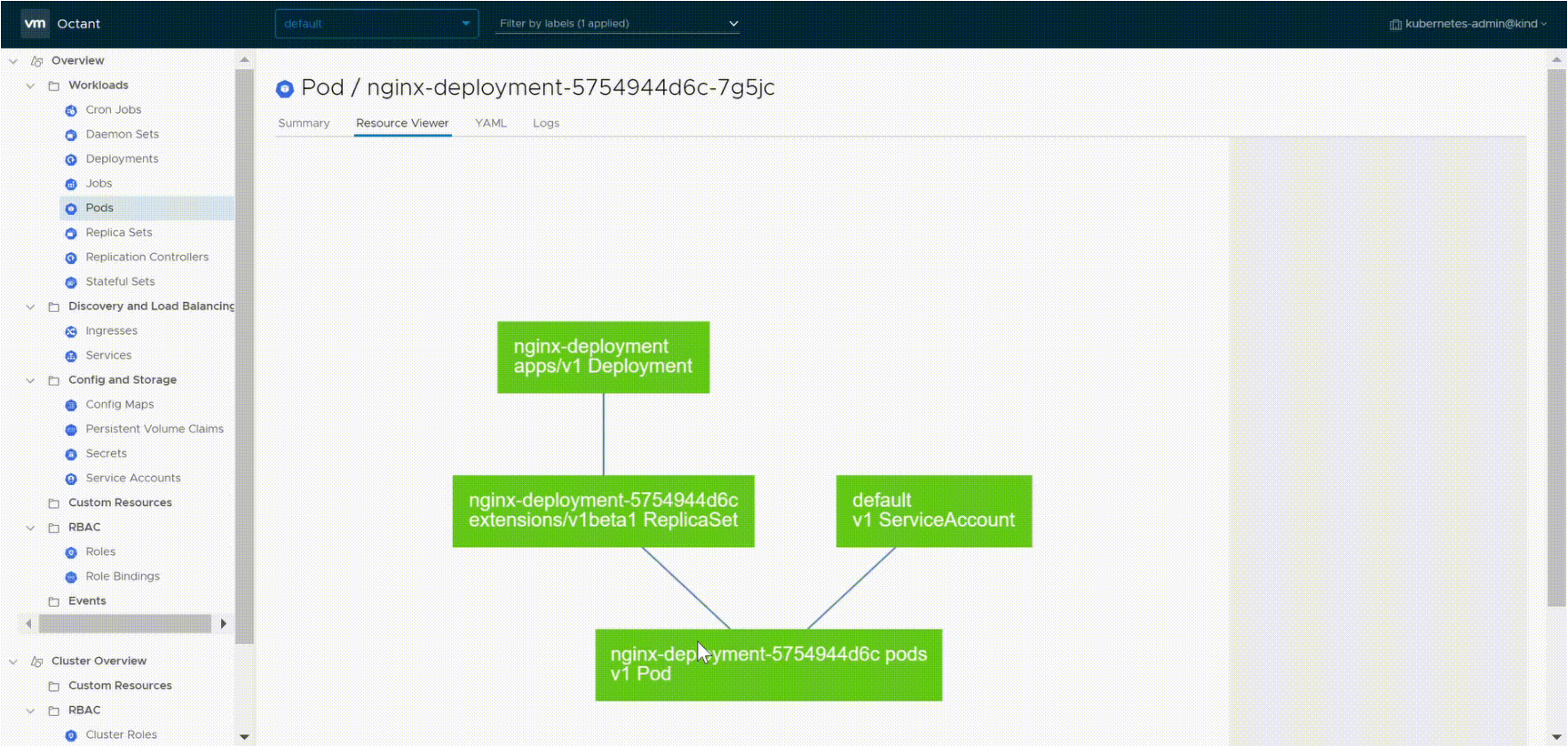

One nice tool for at least seeing how your services are connected is Octant. Octant gives you a visual overview of all of your pods and which services they belong to.

At least with Octant I can easily go from a piece of code to the way that is connected to the internet.

For complex Kubernetes objects like ingresses that behave differently on different cloud platforms, Kubespy is an invaluable tool. Kubespy shows you what is happening under the hood when objects are created. For example, if I create a service it shows which pods at which IP addresses Kubespy will serve traffic to:

> kubespy trace svc test-frontend

[ADDED v1/Service] default/test-frontend

[ADDED v1/Endpoints] default/test-frontend

✅ Directs traffic to the following live Pods:

- [Ready] test-frontend-f6d6ff44-b7jzd @ 192.168.1.1

Logging into a Container and Doing Stuff

A common thing that every developer reaches for is SSH. Maybe in the future, SSH will be as anachronistic as the floppy disk icon, but for now, I want to log in to a container, poke around, see what the state is and maybe run some commands like strace or tcpdump.

Kubernetes doesn’t make this easy. The workflow looks something like this:

kubectl get pods

Look for my pod name

kubectl exec -it $podname -- /bin/bash

Here’s where things get annoying.

> kubectl exec -it dan-test-75d7b88d8f-4p45c -- /bin/bash

OCI runtime exec failed: exec failed: container_linux.go:345: starting container process caused "exec: \"/bin/bash\": stat /bin/bash: no such file or directory": unknown

command terminated with exit code 126

What the heck is this? I know that in production I want my container images to be small (both for image push performance and security) but this is a bit much. Fine, let’s live in 1997. Just let me run strace.

# strace

/bin/sh: 1: strace: not found

Ugh. It’s reasonable that this image doesn’t have strace, and kind of reasonable that it doesn’t have bash, but it highlights one of the Kubernetes best practices that makes local development hard: keep your images as small as possible. This is so annoying in dev. I don’t want to have to keep installing strace all afternoon as my container gets restarted.

I also don’t want to add strace to my production image, for security reasons, and also because it would increase the image size I’d be pushing up and down to my registry, which would slow down remote cluster deploys.

One of my favorite tools that solves this problem is Kubebox. Kubebox makes it easy to see all your pods and you just need to press ‘r’ to get a remote shell in to one of them.

Anyways, large images aren’t a problem on local clusters, right?

But I suppose if you really wanted to, you could put strace and bash on all of your development images–because large images aren’t a problem on local clusters, right?

Pushing/pulling images

Pushing bits around on your laptop should be super fast because there’s no need to go out to the network. Unfortunately, here’s where the myriad local Kubernetes setups rear their ugly head once again.

Let’s talk through the happy path: Minikube and Docker for Mac. Both of these setups run a Docker daemon that you can talk to from your local laptop and from inside the Kubernetes cluster. That means that all you need to do to get an image into Kubernetes is to build it; your pod can “pull” it directly from your local registry, and doesn’t need to deal with moving data over the network.

MicroK8s doesn’t ship with a in-cluster registry turned on by default, but it can easily be enabled with a flag.

In contrast KIND is a whole other beast. It has a special command that you use to load images into the cluster, kind load. Unfortunately it is unbearably slow.

$ time kind load docker-image golang:1.12

real 0m39.225s

user 0m0.438s

sys 0m2.159s

This is because KIND copies in every layer of the image and only does very primitive content negotiation. What this means is that if you change just one file in the final 15 KB layer of your 1.5 GB image KIND can copy in the entire 1.5 GB image anyways.

Fortunately the kind folks working on the KIND project have made a bunch of improvements to image loading recently. We’ve also released a proof of concept for running a registry in KIND which should help improve speeds further.

If I’m going to be using a local development environment I tend to go with Docker for Mac or MicroK8s, though as I stated earlier, these days I prefer to do my development in a real cloud Kubernetes cluster. There are also great tools emerging in this space. Garden caches image layers in a remote registry, reducing what needs to be rebuilt by each developer. Tilt with live_update helps me bypass the need to push and pull images altogether so that’s what I use to solve this problem.

Mounts/file Syncing

Even if you can avoid going out to the internet when pushing an image, just building an image can take forever. Especially if you aren’t using multi stage builds, and especially if you are using special development images with extra dependencies. When compared to a hot reloading local JavaScript setup, even the fastest image build can be too slow.

What I want to do is just sync a file up to my pod. Doing this by hand is relatively simple, but tedious:

kubectl cp <file-spec-src> <file-spec-dest>

Plus if your container is restarted for any reason, like if your process crashes or the pod gets evicted, you lose all of your changes.

There are tools like ksync, skaffold and Tilt that can help with this, though they take some investment to get set up.

Logs/Observability/Events

In dev, I want to tail the relevant logs so I can see what I’m doing. Kubernetes doesn’t make that easy. Each Kubernetes pod has its own log that I have to query individually, and each of these can have many containers. Naively, it’s easy to see the logs for just one pod (kubectl logs podname). However, to see an aggregate view, you need to know a lot about how your pods are organized, like which labels apply to which pods in which parts of your app so that you can run a command like kubectl logs -l app=myapp.

Then there’s Kubernetes events, which you watch via an entirely separate command. This sucks because it’s in the event log that I’ll find important dev information like if my pod couldn’t be scheduled or the new image I pushed up can’t be exec’d.

There’s a great set of observability tools I can use that help with this in production, but I don’t want to be running them locally. Sometimes I can’t afford the resources–my laptop is rather constrained. And while those tools are each excellent in their niche, I’d rather have one tool that makes it easy to do common tasks. In other words, I should always be able to start my debugging in one window. Some problems may be so unique or special that I end up going to other tools to resolve them, but I can’t be having to tab through twelve windows just to check for one problem.

I explore this problem in a different blog post, and I think Tilt solves this well especially now that it includes Kubernetes events alongside pod logs. The aforementioned Kubebox and garden are two other great options.

Conclusion

While developing on Kubernetes still sucks, we’ve come a long way just in the past year. The biggest remaining hole that is begging for a solution is networking. If we want to empower developers to create end-to-end full stack microservices architectures we need to provide some way to get their hands dirty with networking. Until then that last push to production will always reveal hidden networking issues.