Tips on Moving your Dev Env from Docker Compose to Kubernetes

When I first started learning how to write Kubernetes configs, I would sometimes complain to people about it. “They’re so complicated!” they would complain back.

They would show me an example. Here’s a simple Docker Compose config:

app:

image: tilt.dev/simple-node-app

ports:

- 8000:8000

command: sh -c 'node server.js'

And here’s the equivalent Kubernetes config:

apiVersion: apps/v1

kind: Deployment

metadata:

labels:

app: simple-node-app

name: simple-node-app

spec:

selector:

matchLabels:

app: simple-node-app

template:

metadata:

labels:

app: simple-node-app

spec:

containers:

- command: ["sh", "-c", "node server.js"]

image: tilt.dev/simple-node-app

name: app

ports:

- containerPort: 8000

“Why can’t Kubernetes configs be as simple as my Docker Compose configs?”

After two years of playing around with both of them, I think I’ve figured out the answer!!

Kubernetes configs force us to handle change.

When I write the Docker Compose file, I get to optimize for a world where:

- Our servers only run on a single machine

- One instance of each server runs at a time

- When I reload, I stop all the servers and start them all up again

When I write a Kubernetes file, I have to think about how to upgrade that system:

- Our servers could run on different machines

- A new version of a server can gracefully replace an older version

- Each component is independently replaceable. We can replace each server process without touching the others, and redirect traffic without touching the server processes

Most Docker Compose files we see are small. That makes them easy to start! But they also don’t give you the right tools for managing updates and complexity. Once a Docker Compose file grows beyond a certain size, it becomes a tangled mess that no one can touch without breaking. Teams end up replacing their big Docker Compose files with someting else. It’s survivorship bias in action.

I’ve met many teams whose Docker Compose files are in this state. They hope that migrating to Kubernetes configs will make it easier to maintain. But they’re not sure where to start!

Where Not to Start: Pods

A good strategy is to start with a minimum viable migration, verify that it works, then iterate. But a big mistake people make is how they define “minimum”:

-

I have a Docker Compose file with several apps.

-

The minimum Kubernetes primitive for a single running app is a pod.

-

Therefore, I should convert all app configs to Pod configs and see if it works end-to-end.

Don’t do this!

A pod is a good building block but a terrible dev experience.

When you replace a Pod, Kubernetes will, in serial, signal the process to shut down, gracefully wait for it to exit, free all the pod resources, and then start your new Pod. If you’re iterating on your config, this process will be too slow.

But with a bit of planning, Kubernetes can parallelize these steps. It can run the new process and the old process side-by-side, directing traffic to the new server while the old one is shutting down.

Key Insight: Play to Kubernetes’ Strengths

Kubernetes is good at incremental updates, independent components, and reusability. How can we take advantage of that?

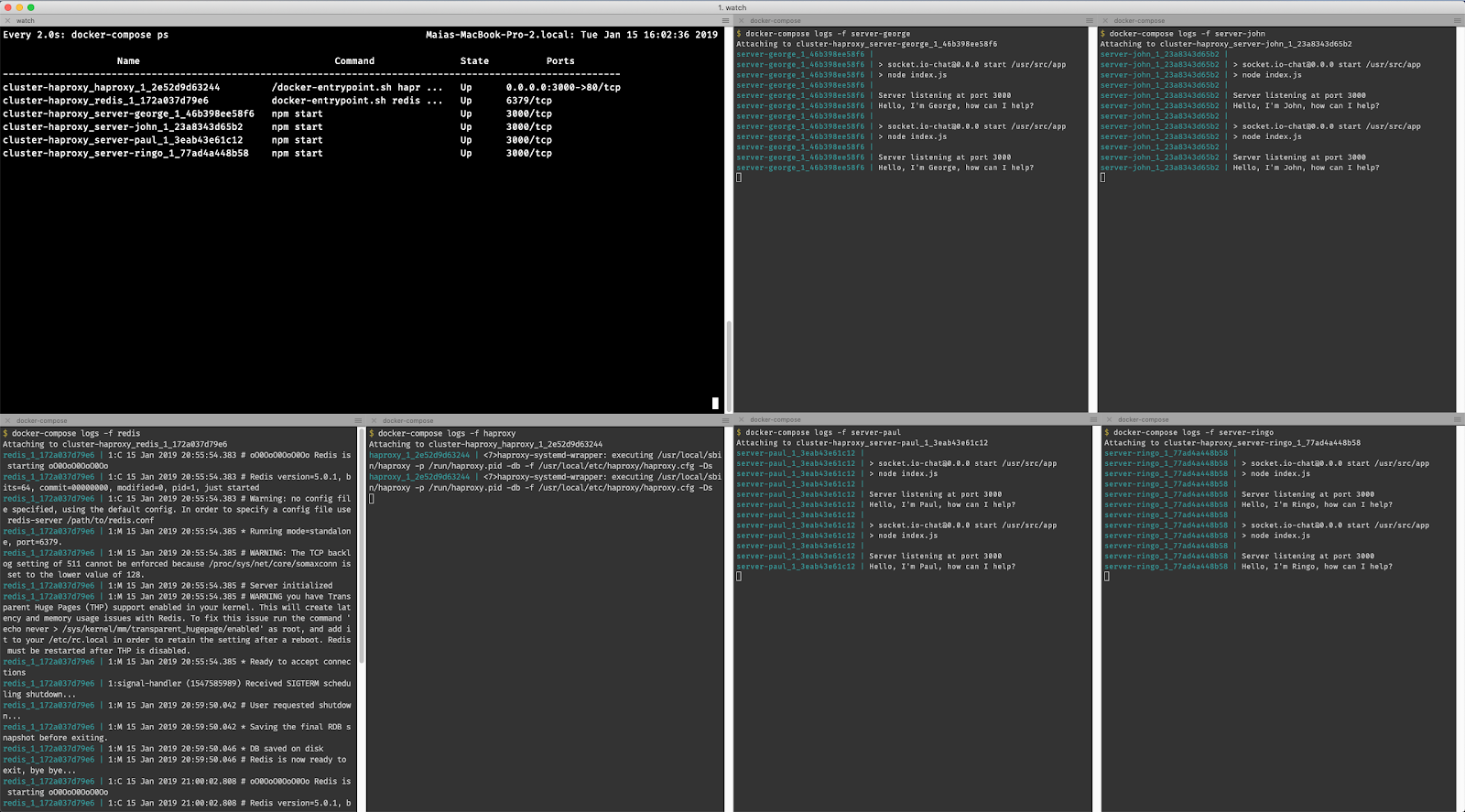

Step 1) Start with a docker-compose.yml file

You can look at the one in our sample repo

Step 2) Run kompose convert

Kompose is a tool that helps convert Docker Compose configs to Kubernetes configs.

Kompose will create a Deployment YAML and Service YAML for each app.

They won’t work. Don’t Panic! That’s OK.

Kompose has lots of bugs. It’s still using beta Kubernetes Deployments by default and seems unmaintained. For most projects, it won’t be a complete solution. But it’s still a great start to build from.

Step 3) Get a “base” service working

Find a base service that doesn’t depend on any other services. Make sure it has

both a Deployment (for running the server process) and a Service (for

directing traffic to that process).

Deploy it to a local Kubernetes cluster. Tweak the Kubernetes configs and keep

kubectl apply-ing until it’s running. Use

kubectl port-forward

to connect the service to a port on your machine, and test it manually with a

browser.

If you get stuck, kubespy trace

is a great tool for checking common misconfigurations.

Step 4) Get a service the depends on “base” working

Find a service that only depends on your base service. This is a good way to explore how networking works in Kubernetes.

Keep kubectl apply-ing it until it’s running OK, just like you did in Step 3.

Repeat until all services work!

Step 5) Throw docker-compose.yml away

This is a good time to throw a party.

How Tilt Can Help

One of the big reasons we made Tilt is to make it easier to iteratively hack on YAML files. The workflow I use:

- Create a Tiltfile with the new K8s configs behind an

ifbranch, so that I can check them in one at a time without affecting teammates using Docker Compose. - Leave Tilt running while I hack on YAML files, so that Tilt continuously redeploys them

- Add port-forwards to the Tiltfile, so that I can look at the services with

a browser without manually invoking

kubectl port-forwardfor each new pod.

Here’s an example Tiltfile I was noodling on while writing this blog post.

Building maintainable cloud-native dev envs is hard. We want to make it easier!