Does This Build Cache Spark Joy?

Pruning Away your Docker Disk Space Woes

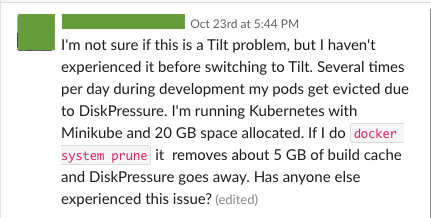

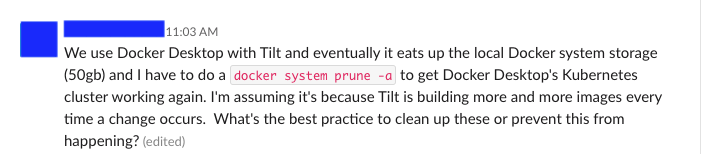

My favorite class of bugs is the one that users run into when they’re using your product too much. If you’ve been using Tilt for a while and so Tilt has been building lots of Docker images for you and it’s starting to eat up your disk space, it can be super frustrating, of course—but when a bunch of people started reporting this problem, I’ll admit that I was a little excited.

If you’re experiencing Docker disk space woes (whether you’re developing on Tilt or not), you’re not alone. This post digs into the signs and causes of disk space issues, tells you how to fix them yourself, and describes Tilt’s new way of handling these problems.

Dude, where’s my disk space?

How to tell you’re in storage trouble

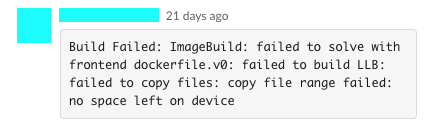

How do you know that you’re running into disk space trouble? The surest sign is that your Docker daemon is throwing errors of the form:

No space left on device

This error can happen in the course of many different operations, but generally it means the same thing: your Docker daemon doesn’t have enough room for all the junk that’s on it.

The more opaque form of this error is when you’re running MacOS and your local Kubernetes cluster (e.g. Kubernetes for Docker for Mac, or Minikube, if you’re also using the Minikube Docker instance) starts throwing “DiskPressure” errors. Recall that local k8s clusters are (generally) single-node clusters, and on MacOS, your nodes are all VMs; thus, all the k8s stuff happening on a single VM. Funnily, all your Docker storage is also on that same VM; thus, if you have too much junk in your Docker storage, it takes away space that k8s would otherwise want to use, so k8s starts complaining about a lack of space. I won’t say that this is always the case, but often, “DiskPressure” errors on your local k8s cluster are, at their root, Docker disk space problems, and not k8s specific; try the steps below and see if the errors go away.

What’s eating you(r disk space)?

If you think you’re running out of Docker storage space, dig in with docker system df to see where your space is going (try -v for even more info). You’ll see stats for four types of Docker objects. I haven’t had to battle volume bloat much, so I’m not going to talk about it here, but let’s talk about the other three objects:

Images: okay, if you use Docker, you probably know what an image is, and it’s probably pretty to easy to imagine how, if you have enough of them, they start taking up a lot of disk space. Because images are composed of layers (see below), an image only takes up size according to its unique layers—but this can still add up. If you’re developing with Tilt, especially if you’re not using Live Update and are doing a fresh docker build for every code change, you’ll be building a lot of images. Sorry about that!

Build Cache: Docker images are composed of layers stacked on top of each other, each layer representing the filesystem state that resulted from a Dockerfile step. (For more on layers, see the docs.) If nothing has changed in layer X, we can reuse the layer X we have lying around from last time and save ourselves time and work. Layers from past builds live in the cache. Usually, this is great—it increases the probability that whenever we’re building a new image, we can reuse something from before.

Containers: if you have a lot of containers around, either running or stopped, they can start to eat up your space, especially if you’ve got big files on them. If you tend to spin up k8s resources and then forget about them, those containers could be causing you unnecessary trouble. With K8s, though, at least when you bring down a pod, its container is removed; some other container management systems (e.g. Docker Compose) will stop but not remove the container, so you still have to contend with its size in storage.

Docker does all this (retaining a cache, keeping old images around) in order to be fast, and usually that’s great! But sometimes it goes too far; when Docker hoards too much old stuff just in case we need it later, it may run out of room to do the work we actually need it to do.

Get that disk space back!

Luckily, there are a number of prune commands that you can run to get rid of all the old Docker artifacts that you don’t actually need anymore and reclaim your precious, precious disk space. (Note that docker system df has a “reclaimable” column that indicates how much of each object can safely be pruned away.)

docker image prune: by default, this command gets rid of all dangling images, i.e. images without tags. (You get dangling images when, say, you had tag myapp:latest pointing to image ID a1b2c3d4, but then you pull down a new version of myapp:latest, such that the tag now points to e5f6g7h8; your old image ID, a1b2c3d4, is now tagless, i.e. dangling.) You can use the --all/-a flag to get rid of unused images as well (i.e. images not associated with a container).

docker builder prune: remove layers from the build cache that aren’t referenced by any images.

docker container prune: remove stopped containers.

You can kill all of your birds (…whales?) with one stone with docker system prune, which basically does all of the above.

It can be especially satisfying to watch your disk usage with watch -d docker system df (you may need to brew install watch) as you prune, and see the numbers drop before your eyes.

How does Tilt deal with this?

Tilt builds a lot of images, and we don’t want you to be sad; that’s why Tilt will periodically prune away your old Docker junk for you. When I sat down to write this feature, I figured it would be a simple matter of:

for {

select {

case <-time.After(time.Hour):

docker.SystemPrune()

}

}

Alas, as is often the case with software, it was much more complicated than that. Some considerations of Tilt’s Docker Pruner:

Don’t prune images/caches the user might want soon

If you’re actively developing on Image X, we don’t want to prune it away, even if it’s not currently running on a container. That’s why Tilt only prunes images/containers of a certain age—by default, 6h or older (you can configure this setting in your Tiltfile). Unfortunately, Docker makes it hard to tell how old an image actually is; the timestamp recorded on an image (and the one respected by the --until filter on prune commands) represents the time the image was first built; if no code has changed, Tilt will build and tag your image, but the build is a no-op and doesn’t change the timestamp. The solution? The metadata.lastTaggedTime field, which gives us an accurate picture of the last time Tilt saw this image.

It would be a pain if you opened your laptop in the morning and started Tilt, and we pruned away last night’s build cache as you were trying to start up new images from it. That’s why we wait until all of your pending builds have finished before we prune, so that you’re sure to have touched any images you’re currently using.

Stay in your lane

We also don’t want running Tilt in one repo to blow away all your caches for another project—which may have totally different Docker Pruner settings, or may not even use Tilt! To make sure we only mess with images built by Tilt, we filter for the builtby:tilt label; to make sure we don’t deal splash damage to your other Tilt projects, we only prune images that the current Tilt run knows about.

Give the user control

By default, Tilt’s Docker Pruner runs once after your initial builds have all completed, and then every hour thereafter, and removes images that are 6 hours old or older. If that doesn’t work for you, don’t worry, you can configure the Docker Pruner settings Tiltfile:

- Not worried about Docker disk space at all? Disable the Docker Pruner entirely!

docker_pruner_settings(disable=True) - If you want to keep your images around for a really long time, adjust the max age of images we keep around:

docker_pruner_settings(max_age_mins=1440) - Say your project eats up a ton of space, and you want to blow away the maximum possible amount of stuff every time; set the max age really low. (Remember that no matter how low you set the max age, we’ll only prune objects that are not in use. So, whatever images you’re currently running are always safe.)

docker_pruner_settings(max_age_mins=15) - Maybe the amount of space you use is unpredictable and doesn’t correlate with time Tilt has been up for; in this case, instead of pruning every X hours, prune every Y builds instead.

docker_pruner_settings(num_builds=10)

We hope the Docker Pruner helps keep your disk usage in check, so you can stay in flow without worrying about finicky errors. Read more about the settings in the docs., configure it to your liking, and let us know how it’s working for you!